National policy to be drafted for sandalwood cultivation and trade

Nitin Gadkari sends a letter to the Union Forest Minister

Perfume and related industry cheers as Indian sandalwood eyes global comeback: Atul Tandon

The ban on cutting, trading, buying, selling, or exporting sandalwood has severely impacted industries such as perfumery, cosmetics, medicine, and incense sticks. The existing blanket ban on the purchase, sale, transportation, and storage of sandalwood stems from the lack of a central sandalwood policy. The absence of a unified approach has severely impacted various sectors despite strong global demand for sandalwood and its oil. The central government initiated a process of developing a central sandalwood policy two years ago, but progress has been slow. In response, Union Minister for Road Transport and Highways, Nitin Gadkari, has urged Union Minister for Forests, Bhupender Yadav, to expedite the creation of central regulations. Indian sandalwood is renowned globally for its superior quality and high-grade oil, distinguishing it from more common varieties available elsewhere. Despite the ongoing illegal trade of sandalwood, which operates with the complicity of bureaucracy and police, law-abiding businesses continue to face substantial obstacles. The perfumery industry remains optimistic about government efforts to establish a sandalwood policy. Gadkari’s letter has been met with enthusiasm by its key stakeholders.

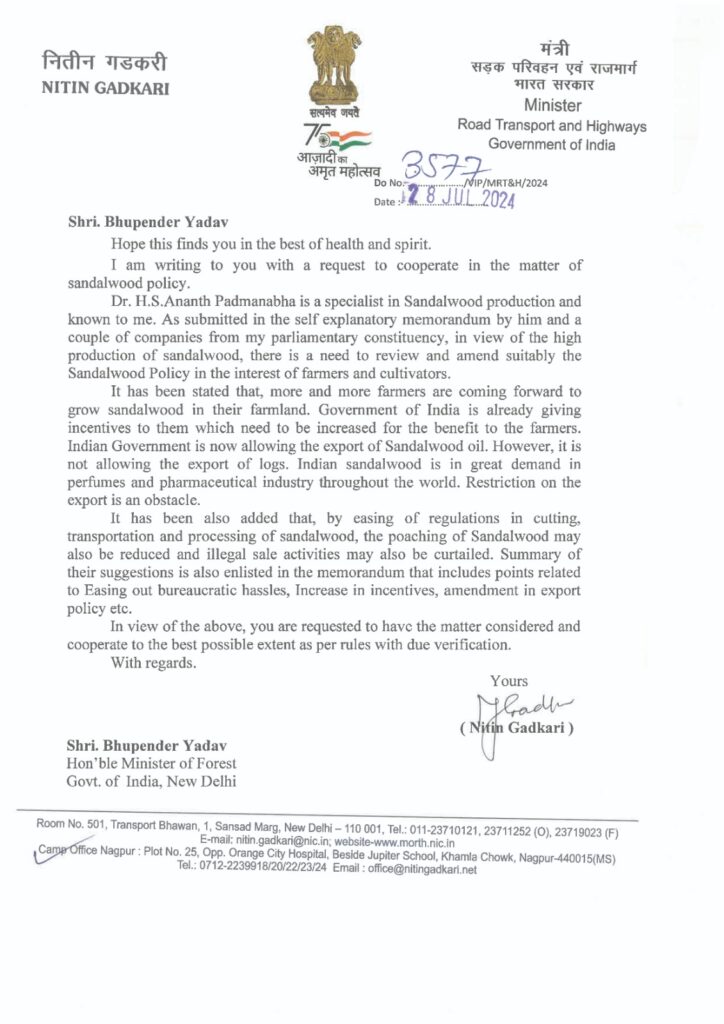

On 28 July 2024, Union Minister Nitin Gadkari addressed a letter to Forest Minister Bhupender Yadav, seeking cooperation on the sandalwood policy issue. He highlighted Dr. H. S. Anant Padmanabh, a renowned expert in sandalwood production, who is well-acquainted with him. According to a memorandum from Dr Anant and several companies in his parliamentary constituency, there is a pressing need to review and amend the sandalwood policy in response to the high production levels in the interests of the farmers. The memorandum reveals that most farmers are eager to cultivate sandalwood on their land. However, the government is already supporting this shift. There is an urgent need to enhance the benefits for these farmers further. The Centre, as of now, permits the export of sandalwood oil but not the wood itself. This restriction, despite the substantial global demand for Indian sandalwood in the perfume, pharmaceutical, and cosmetics industries, creates significant barriers to export. The letter also notes that farmers and industry representatives advocate simplifying regulations related to harvesting, transportation, storage, and sandalwood processing and, to mitigate illegal trade and curb unauthorized sales activities. The memorandum outlines suggestions, including reducing bureaucratic obstacles, offering incentives, and revising export policies. Consequently, Gadkari requests that the matter be reviewed thoroughly and that optimal cooperation be provided, adhering to regulations and proper verification.

Nitin Gadkari has sent detailed information to the Forest Minister from representatives of farmers and industry-based organisations alongside his letter. The memorandum highlights that homegrown sandalwood is acknowledged worldwide for its unique fragrance and multiple benefits. Its powder is used extensively in cosmetics, healthcare, and traditional medicines. The oil plays a crucial role in the perfume industry, as well as in home remedies and cancer therapies. However, illegal harvesting and trade have tarnished this valuable product. All South Indian states have implemented strict security measures to address these issues.

Consumers face a nearly year-long wait to obtain sandalwood powder due to its sensitive nature. Buyers must transport the wood to their warehouse, which requires a transit permit. If the wood comes from another state, this permit must be exchanged at a checkpoint, necessitating the transfer of documentation from the checkpoint to the relevant office in the state capital. This process can take at least one month, and transporting the wood across multiple states may extend the delay to several months. In South Indian states, one needs an import license to buy sandalwood. Some states also require separate licenses for storage, allowing only 2-3 kilograms to be stored. In certain states, the government has a monopoly on the buying, selling, and use of sandalwood.

The memorandum asserts that the proof of authenticity is proper documentation for procuring sandalwood. However, the process involves repetitive and time-consuming procedures at various stages. After the wood is processed, its residue can be used for ritual offerings or as incense powder. Unfortunately, it is classified as sandalwood powder waste. This waste is still subject to forest regulations and cannot be bought or sold. The memorandum underscores that participating in this trade will remain economically unfeasible without streamlining these bureaucratic hurdles.

Homegrown Sandalwood enjoys substantial international demand, presenting significant export opportunities. The techniques for extracting oil and processing sandalwood into various forms are uniquely Indian. Despite this, numerous obstacles hinder the export of sandalwood oil, pieces, powder, and waste powder. Sandalwood is often sourced from the grey market or imported from countries such as Australia, Vietnam, and Indonesia. Simplifying regulations and implementing a central policy could revitalise the Indian sandalwood industry, potentially generating significant foreign exchange for the country. The country imports sandalwood despite its high-quality production capabilities. The memorandum also highlights that farmers are adversely affected by this situation. Sandalwood is an appealing crop, and its cultivation has started in several states. However, farmers face challenges not only from illegal harvesting and theft but also from stringent state regulations. Thus, a central regulation is essential in effectively addressing these issues.

Atul Tandon, head of Malayagiri Sandalwood Oil Distillery, has expressed great enthusiasm regarding the development of a central policy for the sandalwood industry and Nitin Gadkari’s recent correspondence on this matter. His company, a key player in the production and trade of sandalwood wood, oil, essential oil, and vetiver for over 50 years, is eagerly anticipating the policy change. In an exclusive interview with Sugandh India, Tandon noted that two years ago, the central government consulted state governments on sandalwood cultivation and trade to create a central policy, but progress has been notably slow. With Union Minister Nitin Gadkari’s recent intervention, there is renewed hope for faster advancement in this area. Tandon highlighted that the absence of a central policy has forced operations into the shadows, necessitating imports and consequently draining foreign exchange from the country.

He noted that a committee has been established in Bengaluru and is expected to submit its report soon. Once this report is received, it will pave the way for the formulation of a central regulation or law. Currently, varying rules and regulations govern the transportation of sandalwood and its related products across different states. In South India, the storage of sandalwood is restricted to just two to three kilograms. For quantities exceeding this limit, government permission is required to store sandalwood in factories, homes, or warehouses. Consequently, individuals are neither storing nor trading in sandalwood. The Supreme Court had previously mandated the creation of a national law for the sandalwood industry, but this has yet to be implemented.

In response to a question from Sugandh India, Atul Tandon highlighted that, due to restrictions in India, Australia has emerged as a major global hub for sandalwood, despite its quality being significantly inferior to that of Indian sandalwood. Presently, India is falling behind in the global market. The government’s ban on the export of sandalwood oil has benefited Australia and other countries that engage in extensive cultivation and export activities. Before the ban, India earned substantial revenue from the export of 45 tons of sandalwood oil. Tandon expressed optimism that forthcoming regulations may grant ownership rights to sandalwood wood and oil, potentially boosting business opportunities with permissions for storage and export. He noted that although the once-abundant sandalwood forests in parts of Karnataka and Tamil Nadu have dwindled, sandalwood trees can still be cultivated across all states of India. Currently, sandalwood cultivation is underway in Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Assam, and various South Indian states. Tandon added that while a sandalwood tree requires 20 to 25 years to mature, farmers are facing difficulties due to the absence of comprehensive regulations.